Improving soil health practices could transform your soil into a stronger carbon sink

What is carbon capture?

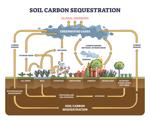

Much like water and nitrogen, carbon has a cycle. Carbon atoms travel from the atmosphere into the Earth and eventually back into the atmosphere. Left to nature’s own devices, this cycle regulates itself. However, humans have released enormous amounts of carbon into the atmosphere faster than the Earth can naturally sequester it. This disruption to the carbon cycle is the primary driver of global climate change.

Humans have nudged the planet in a negative direction. This means we have the power to nudge it in a positive direction. We’re still trying to figure out the best tools to make this happen, and all options are on the table, including carbon capture.

Carbon capture is the act of sequestering carbon as a part of the carbon cycle. Just as human activities can increase the rate at which carbon volatilizes, or releases, into the atmosphere, human activities can increase the rate at which the Earth sequesters carbon. One possible carbon sink, or area where significant amounts of carbon can be stored, is the soil.

Carbon in the soil

It’s impossible to understand the complexity of soil ecosystems by looking at them with the naked eye. Microorganisms and elements interact in diverse ways to create healthy soils. Even for soil scientists like TerraMax CEO Doug Kremer, who’s been studying the soil for decades, some soil microbiome complexities remain a mystery. But using agricultural practices to help sequester carbon merits serious investigation.

“Our current farming styles have changed soil’s ability as a carbon bank,” explains Kremer. “If we alter how we grow plants and treat our soils, we can turn that into a better carbon storage bank. It’s believed that will positively impact global climate change.”

Kremer says, scientists are still learning how strong a role soil could play in this regard. But it is an accepted fact that we can change organic matter in soils. Plant residue digested by microbes provides organic matter for the soil, and agriculture practices can impact this process.

Many soils in the United States are lower in organic matter than they used to be. Appropriate cover cropping and adding plant residue can help restore organic matter, as worms and then microbes break the plant residue down and incorporate it into the soil. This creates a stronger “carbon sink” within the soil.

“In the long run, it will benefit farmers to have a greater appreciation for how they can alter their carbon content, which is how they can build and alter their organic matter,” says Kremer. “This is intimately tied with how their soils can perform.”

Soil health and tilth

Healthy soils mean healthier crops. Also, soil with better tilth, or suitability for growing crops, means healthier crops. Healthy soil should be about 25% air and 25% water, or in other words, 50% open space. This space allows drainage, oxygen exchange, healthy root development and effective nutrient and water transfer to crops. In addition, this available space enables soil microbes to do their jobs at the microscopic level by breaking down organic material into the soil.

The enemy of good soil tilth is soil compaction, where that available space is compressed. Roots that can’t delve as deeply into the soil can’t absorb nutrients or water as well and can’t hold on as firmly. Microbe populations suffer, too, when root systems are stunted by compact soil. This translates into greater costs for growers who must use more water to irrigate their crops and lose crops as they get blown over by strong winds.

“We know how to make soil healthier,” says Kremer. “By not working wet soils whenever possible, and by incorporating plant residue back into the Earth, farmers can increase their soil health and tilth.” One simple way to tell if your soil is healthy is to dig up a shovel full of it. “Soil in good tilth is crumbly,” says Kremer. “The aggregates will break apart easily and have an earthy smell. On the negative side, if your soil has a blocky or prismatic structure, it is too compacted.”

Minimizing negative impacts and taking positive steps

“This is a very holistic environment,” Kremer emphasizes. “And awareness is where it starts.”

By being aware of how farming practices facilitate either positive or negative nudges, growers can act in ways that contribute to the health of their crops and their soils. And, if the carbon capture theory is correct, these small nudges can help the soil become a greater carbon sink. “If we can impact mitigating climate change, that’s important,” says Kremer. “And if we can do that and help a farmer be profitable, that’s a win-win.”